Depression, Fashion, Reaction in the Commentariat.

I remember Robin Williams' diametrically opposed characters in Aladdin and Good Will Hunting with the same fondness, wackiness on one end, sensitivity at the other. Robin Williams' character manifesting in two distinct forms – one didn't contradict the other. Depression amongst well paid funny men and women is no unique phenomenon (considering the pervasiveness of mental illness – 1 in 4 – it would be amazing if this group was somehow excluded), and the cries of why! he was rich! everyone loved him! he was so chipper! show what a mountain we have to climb before we get some understanding about depression and mental health in general.

While some of these comments are just ignorant, there is something poignant and disarming when a comedian kills him/herself. With tragic romantics like Kurt Cobain and Sylvia Plath such introspection seems to logically lead towards total shutdown – but the apparent extroversion, the smiley exterior, of a comedian appears as a shield against depression.

Now's not the time go start psychoanalysing Robin Williams, suffice to say that people are complex – "A guy who made people laugh wasn't a happy guy!? And clouds aren't made from cotton wool??" Every suicide is a failure of society to make allowances for the complexity of people, and support to those who need support. Cries of selfishness or cowardliness straight after the event are the first sign that the message isn't getting through.

There's also the charge that mental illness is somehow fashionable. I have a particular interest in this notion because I think it cuts to the heart of many anxieties of the current age, from the obsession with celebrity to trends in social media to identity politics to moralising about the poor. It is said that creative people are prone to mental illness, and successful people too. Perhaps an illness which 'apparently' lacks physical damage, which appears from the outside to be almost optional, might seem like a useful way to market oneself as a creative genius is this age of self-promotion. A contrarian writer at the Telegraph bemoaned this supposed trend, backed with a report that expressed concern about the medicalisation of society. A psychiatrist he cites wrote, in a short article for the BBC,

A new diagnosis of bipolar disorder might also reflect a person's aspiration for higher social status and a feeling that by having the condition they too are creative.

She referred to an increase in people thinking they might have bipolar disorder following Stephen Fry's announcement that he has it. She related the story of a depressed patient 'self-diagnosing' herself with bipolar disorder. Due to the lean of the article you'd expect to go on to read that this woman was making it all up, just following the fashion, but no.

We later diagnosed her with bipolar disorder.

In fact the article had no evidence, or even a single example, that this was a trend. The editor had however picked out the buzzwords 'celebrity effect' and 'desirable diagnosis' to use as markers throughout the article, showing that this was the message that was to be conveyed. It's pretty poor for the 'unbiased' BBC and a doctor to be feeding the right-wing commentariat like this, sans evidence.

So why the increase in self-diagnosis? Could it be perhaps that Stephen Fry's announcement raised awareness? That it was somehow educational, or helpful, or diffused embarrassment? Since the internet has made self-diagnosis easier, there's been a rise in hypochondria (what they call cyberchondria – very cool name). Does that mean that testicular cancer has become a more 'desirable diagnosis'? Since the Jimmy Saville scandal, reports of sexual violence has increased. Are we to assume they're making it up? Or that they now feel able to discuss it? It's a warped person who immediately assumes it's being made up.

Nowadays, people blog and tweet about their worries, and sometimes think that a Facebook status "– feeling down", or a sad emoticon is an appropriate reflection of their mood. It comes alongside (what reactionary writers see as) a general trend of an increasingly self-involved, lazy and superficial society who've lost their moral integrity, their wartime spirit. The right wing hold on dearly to the notions of individual freedom, choice and responsibility, and anything that challenges these values is suspect. Hence, as that Telegraph article concludes, "It can feel comforting to be diagnosed with a mental illness; it can appear, unrealistically, in my view, as a doctor-approved catch-all explanation for one’s personal troubles, travails and failings."

And voilà! You have yourself a catch-all explanation of why mental illness is common amongst the wretched and feckless poor!

Unneeded medicalisation is a valid concern (big pharmaceutical companies do have this agenda, make no mistake), and there's no doubting that depression has developed a sense of cultural allure that comes with anything mysterious which concerns the human condition. There's a clothing brand called 'depression', exploiting as best as they can the dark aesthetic that goes with low mood. They even have a 'philosophy'.

Unneeded medicalisation is a valid concern (big pharmaceutical companies do have this agenda, make no mistake), and there's no doubting that depression has developed a sense of cultural allure that comes with anything mysterious which concerns the human condition. There's a clothing brand called 'depression', exploiting as best as they can the dark aesthetic that goes with low mood. They even have a 'philosophy'.

But the appeal of melancholia goes back to the Romantic poets, so it's nothing new. Is it different now, with the democratisation of the everyday voice, and the capitalist drive to make everything a consumable item? Is it somehow dangerous, leading to increased teenage suicides following in the wake of their favourite doomed rock idol? Or is it a bit of a myth, just another aspect of human expression? Are people who don't understand assuming that depressed people are suspiciously quick to 'admit' to it, rather than hiding off in a darkened room where they belong?

Depression is not a period of down-in-the-dumpsness. There's a difference between a bit of sadness and depression, and one of the problems is objectively locating a point on this misery spectrum at which one becomes 'depressed'. There is an element of self-diagnosis in depression, it has a variety of causes – largely experiential and cultural, sometimes totally mysterious – and people experience it in different ways. But just as the distinction between sadness and depression is real and significant, marking a categorical difference in the condition, so too is there a categorical difference between aesthetic melancholia of the type satirised with the goth kids on South Park, and depression proper. One is not going to simply 'become depressed' by liking Marilyn Manson and wearing dark clothes.

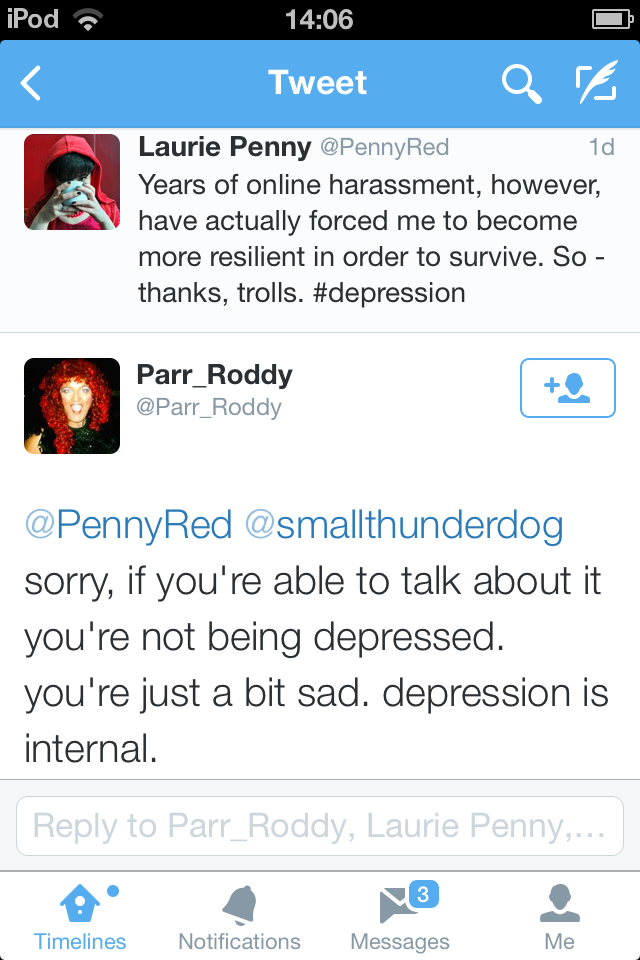

To 'admit' to having anxiety problems has become far more common amongst writers, actors and comedians. As I wrote before, I find the 'strange celebration' of mental illness (as an awareness-raising project) a little irksome, an aspect of personal branding. That's because I'm a cynic myself – I have the same feeling about charity wristbands. Yet overall I think it's a positive discursive shift. A response yesterday to Laurie Penny on Twitter expressed an opinion that I understand, if not agree with.

Of course such a sweeping diagnosis about what 'true' depression is is ridiculous, but that's opinion for you. Both of those tweeters who disagreed with Penny went on to explain, with varying degrees of ferocity, that they had been affected by depression and suicide, personally or in the family. Penny's followers berated them both for their 'ignorance'.

It's not pleasant to see such a reaction made to a difference of opinion which comes from other people's experiences of depression. But then again, Twitter is made for cruel venting. Most give as good as they get.

(And some people just hate Laurie Penny – what's that about?!)

I think people who experience depression tend to find themselves quite isolated, emotionally adrift and misunderstood. The sense of hopelessness is going to feed this impression and deepen it. Arguments will go on about whether depression is a disease, or whether it's cultural, biological or chemical, and so on, but the misunderstandings continue, the ignorance prevails, and often depressed individual exists very much on the periphery of all this chatter.

There seems to be two general responses. One is defiant outrage as seen on Twitter and the SomeOfUs campaign which seeks to hold Fox News to account for their insensitive analysis of Robin Williams. This response uses creative analogies and talk-to-the-hand sarcasm in an attempt to explain depression, and states 'if you've never experienced it, you don't know.' The arguments are sound, but it's a cliquey, belligerent approach and provokes a reaction. It's common on Twitter on many subjects, the (slightly passive aggressive) 'advice' from well-meaning types sent out into the ether. Whilst I agree with the content, I can't help feeling that they're really getting off on expressing it.

There seems to be two general responses. One is defiant outrage as seen on Twitter and the SomeOfUs campaign which seeks to hold Fox News to account for their insensitive analysis of Robin Williams. This response uses creative analogies and talk-to-the-hand sarcasm in an attempt to explain depression, and states 'if you've never experienced it, you don't know.' The arguments are sound, but it's a cliquey, belligerent approach and provokes a reaction. It's common on Twitter on many subjects, the (slightly passive aggressive) 'advice' from well-meaning types sent out into the ether. Whilst I agree with the content, I can't help feeling that they're really getting off on expressing it.

The other is the silent response of those who do not engage. Depression can be a very individual experience, and it's somehow at odds with the idea of a collective community which seeks to change attitudes, in the way that, say, feminism takes up a cause. I think this leads to cynicism from depressed people about other depressed people. Depression is also deeply political, which is in part why there is an interest in dismissing it. If the Left want to 'use' mental illness to fight the establishment, it can't be at the cost of the sufferers – being told that your plight is due to post-Fordist labour conditions, creeping surveillance or the pervasive ontology of competitive capitalism offers little practical help to a depressive on a bad day. (Might be suitable on a good day though).

If there is an element of romanticism about depression then this is a shift in a long-term conversation about a little understood thing, and insofar as the conversation widens, and the dismissive attitude of some is intelligently challenged, then it's not a bad thing. One might seek to understand it in terms of the Hegelian dialectic, a part of historical progress. One might caricature the respective social attitudes as such: 1. mental illness is dangerous (thesis). 2. mental illness is cool (antithesis). Number 3 (synthesis) would be a negation of the antithesis, a kind of resolution.

It makes little sense to me that the epidemic of anti-depressants is caused by a load of oversensitive romantics looking for a bit of sympathy and self-promotion. If someone who isn't really depressed says that they are depressed, it's not really a big deal. The important thing is that people who do have problems feel that the environment is right for them to be able to express it any way that's most comfortable to them. This is undoubtedly very difficult. For that, any celebrity, or any friend, or any stranger, deserves the benefit of the doubt at the very least.